More than 100 million people in the US are living with either diabetes or pre-diabetes, but a staggering one in four don’t know they suffer, being undiagnosed. For those who do, how regularly they track their glucose data depends on the type of diabetes they have and the treatment required. Monitoring is commonly done by taking a drop of blood with a pinprick, but a lot of people track continuously with wearables that measure blood sugar at intervals and relay that information to a smartphone or other device.

The first option is unpleasant and often inconvenient; the second is costly, and still invasive. But there is hope for diabetics to live more comfortable lives in the future.

The first option is unpleasant and often inconvenient; the second is costly, and still invasive. But there is hope for diabetics to live more comfortable lives in the future.

It’s important that continuous trackers get better at offering analytics and support that helps people make management decisions while shrinking in size and growing inconvenience.

It’s important that continuous trackers get better at offering analytics and support that helps people make management decisions while shrinking in size and growing inconvenience.

“Most people with diabetes are not checking themselves enough,” says PKVitality general manager Minh Lê. “It should be a product that you can take with you. It’s a product you can use to check yourself at a meeting without other people seeing it. And it won’t add any pain.” Like other CGMs (continuous glucose monitors) the watch penetrates the skin to the interstitial space, but with an interchangeable module, changed once a month, that sits on the back of the watch and pushes the biochemical sensors under the skin. PKVitality claims its watch is very accurate at +/- 8%, however it is yet to get the clearance from health regulators to put it in the hands of consumers.

The watch is set to cost $150, with a monthly $99 for each capsule. That might seem a lot, but compared to the cost of other CGMs out there – including maintenance to keep them going – it’s far more reasonable. A study found that people with diabetes incur medical costs about 2.3 times higher than those who don’t suffer from the disease. For these people, a device like PKVitality’s could be life-changing. As Lê says, “complications are much more costly than prevention,” and not only would such a device be cheaper over time, it would be less intrusive.

“Most people with diabetes are not checking themselves enough,” says PKVitality general manager Minh Lê. “It should be a product that you can take with you. It’s a product you can use to check yourself at a meeting without other people seeing it. And it won’t add any pain.” Like other CGMs (continuous glucose monitors) the watch penetrates the skin to the interstitial space, but with an interchangeable module, changed once a month, that sits on the back of the watch and pushes the biochemical sensors under the skin. PKVitality claims its watch is very accurate at +/- 8%, however it is yet to get the clearance from health regulators to put it in the hands of consumers.

The watch is set to cost $150, with a monthly $99 for each capsule. That might seem a lot, but compared to the cost of other CGMs out there – including maintenance to keep them going – it’s far more reasonable. A study found that people with diabetes incur medical costs about 2.3 times higher than those who don’t suffer from the disease. For these people, a device like PKVitality’s could be life-changing. As Lê says, “complications are much more costly than prevention,” and not only would such a device be cheaper over time, it would be less intrusive.

Google was also working on a contact lens for tracking glucose noninvasively from the eye, but the project has gone suspiciously quiet.

Unlike the optical-based sensor baked into the Apple Watch, EKG (electrocardiogram technology, which detects the electrical activity produced by a heartbeat) is still considered the most accurate way to record heart rate activity. It’s used by the medical industry and found inside heart rate monitor chest straps. The technology taps into AI and when combined with the Watch’s heart rate data and activity sensors will evaluate the correlation between heart activity and physical activity. When the two are out of sync, the device will alert users to capture EKG data.

Google was also working on a contact lens for tracking glucose noninvasively from the eye, but the project has gone suspiciously quiet.

Unlike the optical-based sensor baked into the Apple Watch, EKG (electrocardiogram technology, which detects the electrical activity produced by a heartbeat) is still considered the most accurate way to record heart rate activity. It’s used by the medical industry and found inside heart rate monitor chest straps. The technology taps into AI and when combined with the Watch’s heart rate data and activity sensors will evaluate the correlation between heart activity and physical activity. When the two are out of sync, the device will alert users to capture EKG data.

How does it work? Essentially, it’s going off an idea that was established in a 2005 study that showed a correlation between heart rate variability and diabetes. It works like this: As your body develops insulin resistance, your sympathetic nervous system gets hyperactive and your parasympathetic nervous system withdraws. This causes an imbalance in your overall nervous system.

However, Cardiogram doesn’t think DeepHeart will be used to actually diagnose diabetes. Instead, it believes that heart rate sensors are best used to alert users of high risk. Just because heart rate variability is physiologically related to diabetes, it doesn’t mean a diagnosis is appropriate.

How does it work? Essentially, it’s going off an idea that was established in a 2005 study that showed a correlation between heart rate variability and diabetes. It works like this: As your body develops insulin resistance, your sympathetic nervous system gets hyperactive and your parasympathetic nervous system withdraws. This causes an imbalance in your overall nervous system.

However, Cardiogram doesn’t think DeepHeart will be used to actually diagnose diabetes. Instead, it believes that heart rate sensors are best used to alert users of high risk. Just because heart rate variability is physiologically related to diabetes, it doesn’t mean a diagnosis is appropriate.

The first option is unpleasant and often inconvenient; the second is costly, and still invasive. But there is hope for diabetics to live more comfortable lives in the future.

The first option is unpleasant and often inconvenient; the second is costly, and still invasive. But there is hope for diabetics to live more comfortable lives in the future.

Wearables using Invasive testing techniques

Right now, invasive techniques can tell diabetics what insulin dosage they need by measuring their blood and interstitial fluid. This can be done by pricking the skin for blood, or tracking interstitial fluid just beneath the surface, as Dexcom’s devices do. Dexcom, one of the biggest names in continuous glucose monitoring, produces devices used by 200,000 people worldwide. Dexcom’s wearable tracker is made of two parts: a disposable needle that goes just under the skin to monitor interstitial fluid; and a patch that sits on top, housing the electronics that measure the sensor and transmit them to a Bluetooth device. Most continuous trackers on the market read from this interstitial fluid, as blood glucose diffuses very quickly into it, making it highly indicative of exact levels at any given time. People can look at the readings from the device and determine if they should eat carbohydrates or take their insulin. It’s important that continuous trackers get better at offering analytics and support that helps people make management decisions while shrinking in size and growing inconvenience.

It’s important that continuous trackers get better at offering analytics and support that helps people make management decisions while shrinking in size and growing inconvenience.

Could a smartwatch one day perform the same task?

French company PKVitality believes so and has a device called the K’Track Glucose in the works to prove it. “Most people with diabetes are not checking themselves enough,” says PKVitality general manager Minh Lê. “It should be a product that you can take with you. It’s a product you can use to check yourself at a meeting without other people seeing it. And it won’t add any pain.” Like other CGMs (continuous glucose monitors) the watch penetrates the skin to the interstitial space, but with an interchangeable module, changed once a month, that sits on the back of the watch and pushes the biochemical sensors under the skin. PKVitality claims its watch is very accurate at +/- 8%, however it is yet to get the clearance from health regulators to put it in the hands of consumers.

The watch is set to cost $150, with a monthly $99 for each capsule. That might seem a lot, but compared to the cost of other CGMs out there – including maintenance to keep them going – it’s far more reasonable. A study found that people with diabetes incur medical costs about 2.3 times higher than those who don’t suffer from the disease. For these people, a device like PKVitality’s could be life-changing. As Lê says, “complications are much more costly than prevention,” and not only would such a device be cheaper over time, it would be less intrusive.

“Most people with diabetes are not checking themselves enough,” says PKVitality general manager Minh Lê. “It should be a product that you can take with you. It’s a product you can use to check yourself at a meeting without other people seeing it. And it won’t add any pain.” Like other CGMs (continuous glucose monitors) the watch penetrates the skin to the interstitial space, but with an interchangeable module, changed once a month, that sits on the back of the watch and pushes the biochemical sensors under the skin. PKVitality claims its watch is very accurate at +/- 8%, however it is yet to get the clearance from health regulators to put it in the hands of consumers.

The watch is set to cost $150, with a monthly $99 for each capsule. That might seem a lot, but compared to the cost of other CGMs out there – including maintenance to keep them going – it’s far more reasonable. A study found that people with diabetes incur medical costs about 2.3 times higher than those who don’t suffer from the disease. For these people, a device like PKVitality’s could be life-changing. As Lê says, “complications are much more costly than prevention,” and not only would such a device be cheaper over time, it would be less intrusive.

Wearables using Non-Invasive testing techniques

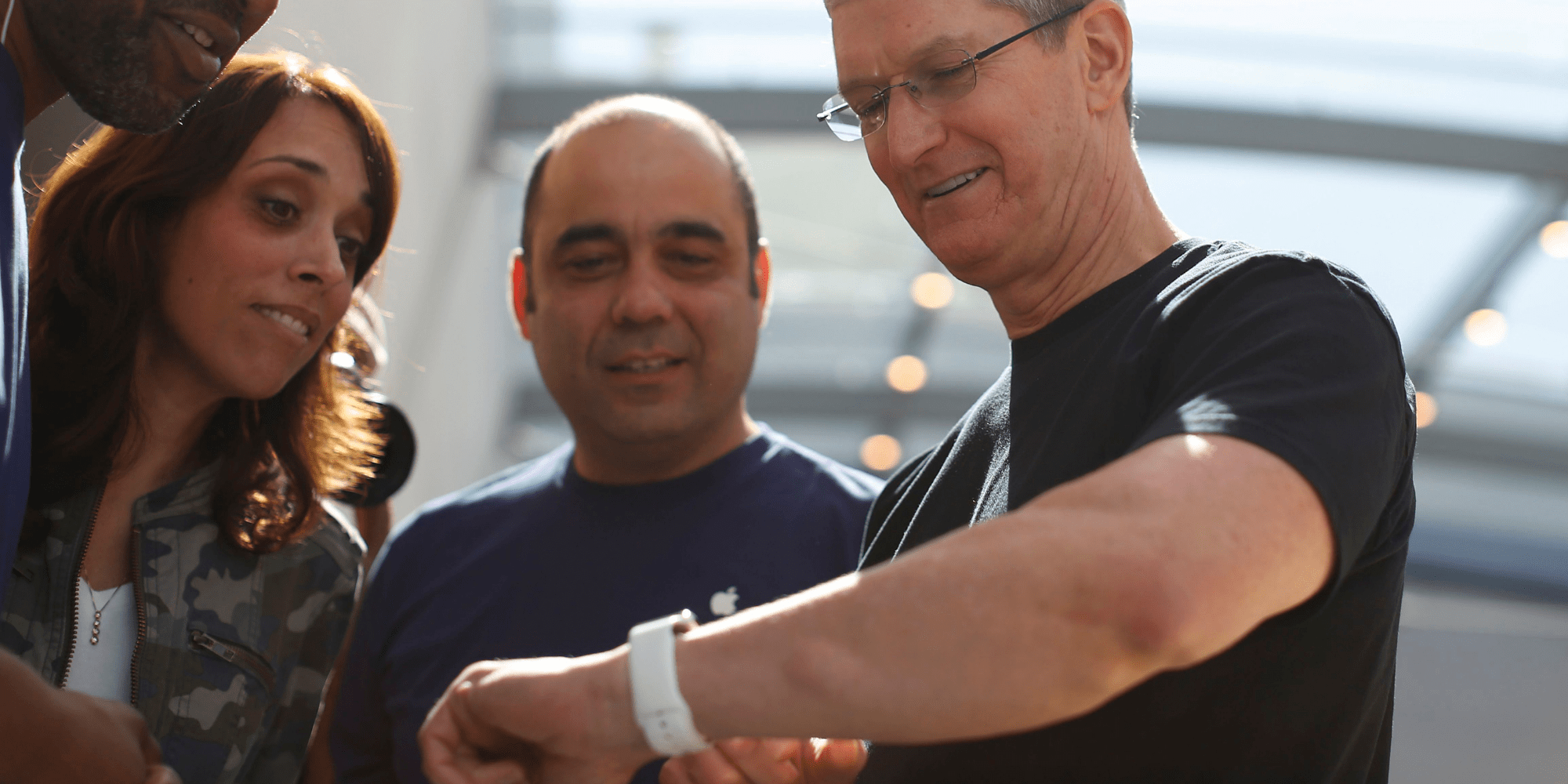

Non-invasive testing, where the skin isn’t penetrated at all, is the holy grail of glucose monitoring and diabetics. Speculation continues that Apple, Google, and others are looking to produce non-invasive means to tracking glucose, but it seems unlikely it can do this without a significant leap in technology. Apple is reported to have a team busily researching the possibility of non-invasive techniques, presumably with the hope it could offer this feature in the Apple Watch. Google was also working on a contact lens for tracking glucose noninvasively from the eye, but the project has gone suspiciously quiet.

Unlike the optical-based sensor baked into the Apple Watch, EKG (electrocardiogram technology, which detects the electrical activity produced by a heartbeat) is still considered the most accurate way to record heart rate activity. It’s used by the medical industry and found inside heart rate monitor chest straps. The technology taps into AI and when combined with the Watch’s heart rate data and activity sensors will evaluate the correlation between heart activity and physical activity. When the two are out of sync, the device will alert users to capture EKG data.

Google was also working on a contact lens for tracking glucose noninvasively from the eye, but the project has gone suspiciously quiet.

Unlike the optical-based sensor baked into the Apple Watch, EKG (electrocardiogram technology, which detects the electrical activity produced by a heartbeat) is still considered the most accurate way to record heart rate activity. It’s used by the medical industry and found inside heart rate monitor chest straps. The technology taps into AI and when combined with the Watch’s heart rate data and activity sensors will evaluate the correlation between heart activity and physical activity. When the two are out of sync, the device will alert users to capture EKG data.

Can heart rate sensor detect Diabetes?

High or low heart rates could be signs of a serious condition. But many people don’t recognize the symptoms, so the underlying causes often go undiagnosed. Heart rate sensors check your heart and alert you to these irregularities — so you can take immediate action and consult your doctor. Cardiogram, a heart rate tech company, believes it may have found the answer in the heart rate sensor, inbuilt in many smartwatches and fitness trackers. It published a study showing that it can use heart rate variability in existing HR sensors to detect if someone has diabetes with 85% accuracy. However, the company is explicit about the fact this is only for detecting signs for the condition, not diagnosing – and certainly not being able to advise diabetics on their insulin requirements. The key to Cardiogram’s success is DeepHeart, its neural network that can be used to quickly – and accurately – sift through data to find patterns and surface potential problems. How does it work? Essentially, it’s going off an idea that was established in a 2005 study that showed a correlation between heart rate variability and diabetes. It works like this: As your body develops insulin resistance, your sympathetic nervous system gets hyperactive and your parasympathetic nervous system withdraws. This causes an imbalance in your overall nervous system.

However, Cardiogram doesn’t think DeepHeart will be used to actually diagnose diabetes. Instead, it believes that heart rate sensors are best used to alert users of high risk. Just because heart rate variability is physiologically related to diabetes, it doesn’t mean a diagnosis is appropriate.

How does it work? Essentially, it’s going off an idea that was established in a 2005 study that showed a correlation between heart rate variability and diabetes. It works like this: As your body develops insulin resistance, your sympathetic nervous system gets hyperactive and your parasympathetic nervous system withdraws. This causes an imbalance in your overall nervous system.

However, Cardiogram doesn’t think DeepHeart will be used to actually diagnose diabetes. Instead, it believes that heart rate sensors are best used to alert users of high risk. Just because heart rate variability is physiologically related to diabetes, it doesn’t mean a diagnosis is appropriate.